Building a background for virtual production

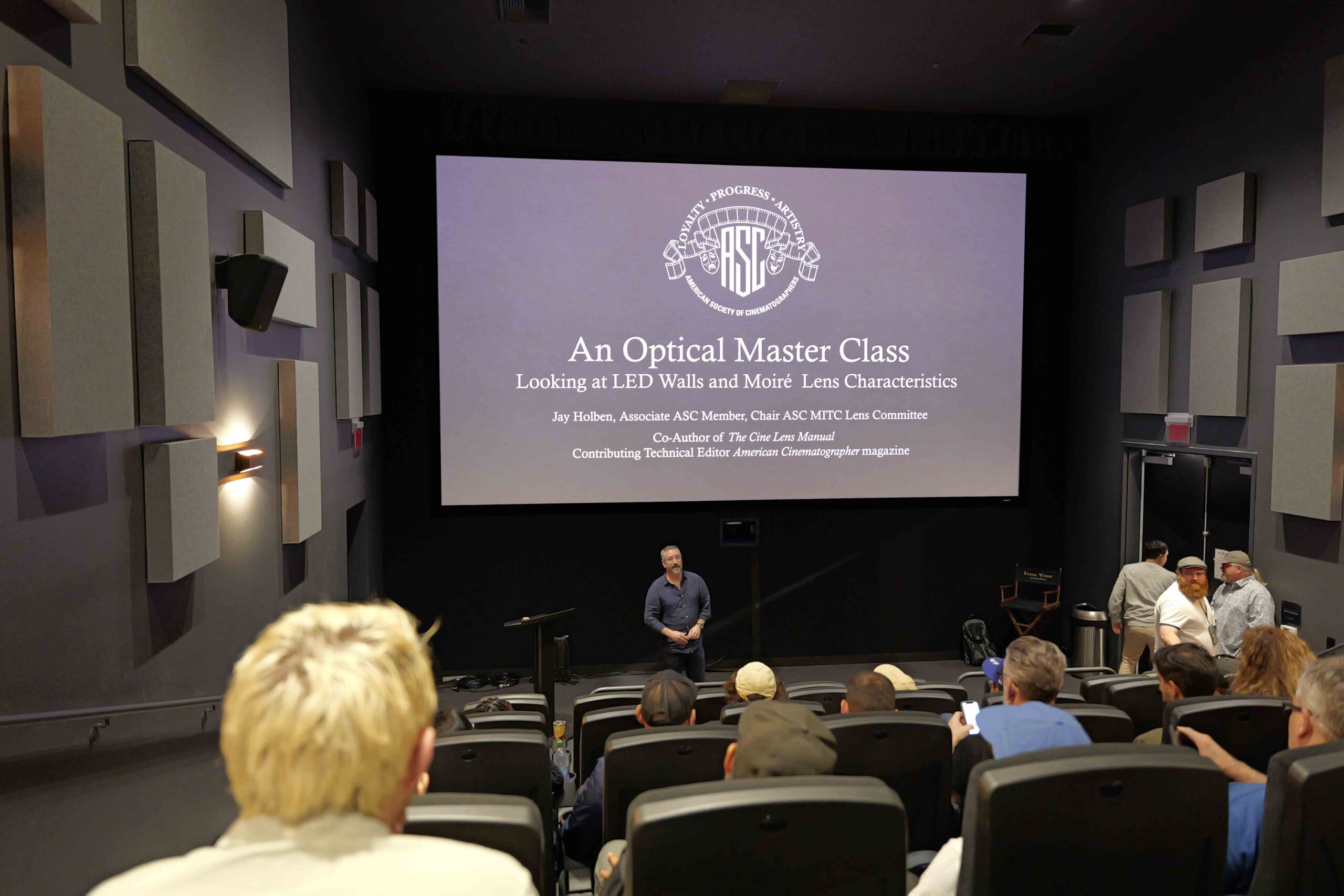

In late June, The American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) hosted a master class focused on virtual production. Attending this class was a small group of cinematographers from all over the world, being instructed by industry experts and renowned ASC cinematographers. Over the course of one week, these students, including myself, would dive deeply into the mind-bending technology behind virtual production.

Before going forward, it might be worth visiting The Virtual Production Glossary for any terms you might want more clarification on.

Jay Holben and the Nyqusit Limit

The first performers in any event have the hardest job because they set the tone and lay the foundation for the kind of experience that the audience will have throughout the show. It’s the same for a multi-day class with multiple instructors. Luckily Jay Holben came to the stage ready to go. As a director, producer, “recovering cinematographer” and co-author of The Cine Lens Manual, Jay has a wealth of knowledge.

One the fundamental takeaways of his lecture was how optics and their characteristics can determine how convincing the illusion of shooting on an LED wall is. Specifically, how moiré plays a role in that equation.

Moiré appears when shooting very fine detailed patterns. When the pattern is in sharp focus, imperfections such as color aberrations and visual misalignments of the same pattern will appear. During virtual production, this can cause issues when the pitch of the LEDs on the volume wall cause visible patterns that are not meant to be there. It ruins the illusion and makes the viewer aware of the fact that it is all fake.

So how do we counter moiré and raise the base of the Nyquist Limit? Low-pass filters employed in some cinema cameras can help cut the amount of high-frequency detail coming from the volume wall. Another method is by using lenses that are technically imperfect. Because some optics have characteristics that “smudge” the image, they can be useful in helping hide artifacts and therefore help sell the illusion. Using very fast lenses is also an option. By shooting with a much more shallow depth of field, you can push the wall out of focus and blend patterns together.

Note: It’s interesting to keep in mind that shooting with film removes this issue because it is an organic medium. These steps are only necessary when working with digital sensors.

ARRI rental hosted the attendees in their volume studio for the remaining portion of Jay’s presentation, where we experimented with a optic lover’s fantasy lens selection. There were optics from every manufacturer (including SIGMA, of course). Spherical and anamorphic. There was a healthy collection of filter options as well.

This was my first time interacting with a fully operational stage, and I was incredibly impressed at how detailed the screen was. Unreal Engine, the video game developing software, is responsible for many of the best games ever made, so it shouldn’t have been surprising to see how realistic and interactive the environment was, but it really did impress. Every element in the environment can be manually manipulated by the operator. Lighting, color temperature, and even depth of field is customizable and can be tailored to fit the needs of production.

Magicbox – A studio on wheels

The common perception is that virtual production happens on enormous stages with LED walls stretching as far as a football field. Magicbox’s mission is to change that. Built to bring accessibility and mobility to this workflow, Magicbox offers a fully functioning virtual set within the footprint of a semi-truck shipping container. During our presentation, it was in a car plate configuration with a rotatable floor. In this setup, shooting vehicle scenes can be accomplished in a fraction of the time. As the saying goes, time is money. And frankly, money is money. By not needing to gather permits, close public streets, and hire bigger crews, a production can stay more efficient. In my opinion, situations like these are where virtual production really shines. To be able to replicate shots indefinitely with the same lighting, environmental placing and overall continuity is incredibly valuable.

By nature, virtual production is very technical. In that regard, there is some fear that naturally occurs whenever cinematographers come into virtual production for the first time. However, ASC cinematographer Michael Goi encourages filmmakers to fall back on our fundamentals. In a quote that appeared throughout the course, Michael says, “We use complicated technology with old techniques.” We should tackle working with a volume wall the same way we go into any set, and also allow for imperfections to appear in order to draw the audience into the scene and allow them to accept the magic trick.

Michael introduced us to the term frustrum – a square that is linked to camera placement and adjusts to the FOV perspective of the lens being used. It is linked through tools such as IR tracking.

Ready, set, launch with Orbital Studios

The remainder of the course was held at Orbital Studios located in the Arts District in Los Angeles. Since opening, Orbital has used their expertise in virtual production to help their clients bring their visions to life.

Leo Jaramillo is the in-house cinematographer at Orbital Studios. He was gracious enough to share his experience by answering a few of my questions:

**********

Frank Ramirez (SIGMA): What is Orbital Studios’ focus?

Leo Jaramillo (Orbital Studios): We are an ICVFX solutions company. In the myriad of different attributes LED wall technology can be utilized, there are just as many situations and infrastructure to support it. We offer solutions to these challenges. For some clients, we offer full VAD and Virtual Production workflow, and yet others need integration and installation of LED walls for their own facilities. We can be remote or have stages here at 667. The screens travel as well as the braintrust, expertise, and the hardware to handle the most robust filmmaking scenarios.

Frank: How do you see virtual production evolving in the next few years?

Leo: Today, A.I. seems to grip the imagination and the forefront of most industries. It’s the same within the film industry. As these contracts get sorted, one thing is abundantly clear; the cost of content seems to be getting more budget conscious, especially for locations. But virtual production can provide an alternative to location shooting, as well as the time it takes to do that. Building the lion’s share of sets in virtual, as well as shaving days or weeks off production schedules, could be an advantage that a production needs. Virtual production works regardless of utilizing AI, or not, so it’s independent of those factors.

Frank: What kind of productions stand to benefit most from this kind of workflow?

Leo: Any production that requires multiple sets and locations, or any production that has limited time with their main actors’ availability, or any driving sequence that needs to be done safely, or any production that needs to build a limited number of sets due to construction costs. In short, there isn’t a scenario out there that couldn’t use virtual production. There are just such an enormous amount of solutions and applications.

Frank: How should a cinematographer who has no experience with an LED volume take the first virtual step?

Leo: I get this question so much. And the answer is absolutely simple. Know lighting. I know it’s strange, but often times cinematographers who do not know how to light will find themselves in the dark about how to do it in a volume. In a traditional location, much of the ambience, and directional light is baked in, unless of course you alter it. Knowing what is “believable” as a replication of the asset in the physical space of your volume is tantamount to the magic trick. A solid background in lighting is the single most important thing to understanding matching the live action with the unreal.

Frank: Are there any VP standards or guidelines that you follow for shooting on set?

Leo: I look at the assets as soon as possible with the Unreal Operator. Regardless of what the director is going to shoot in that space, I make sure we have all the lighting options available for translating that look and light of the asset into the physical world. There are idiosyncrasies about shooting volumes that are only gatekeepers here on one of these stages. There are several other ecosystems in play namely, tracking. When we shoot 3D environments, tracking can be a problem in regards to occlusions, so you cannot just light anywhere. Being cognizant of these pitfalls takes another level of lighting since you may have to switch out the instrument you normally would use for one that is still doing what you want but having a different profile or position.

Frank: How important is lens choice when shooting on the volume?

Leo: Namely, speed. Camera frustums are live tracked vantage points of the camera that are making adjustments in real time. The tighter the frame, the tighter the frustum. So more processing power can go to the image. However, here at Orbital, I’ve gotten as wide as an 18mm Anamorphic lens. We have a robust computer network here to handle 22K files and tracking in real time across 60 and 100-foot walls.

Frank: How has SIGMA been a help in your work and tests when shooting on a volume set?

Leo: SIGMA [CINE] lenses have been extremely reliable and sharp. They are what we have here as a go-to for lenses. I chose them specifically of where they sit along the spectrum of character to commercial. And they seem to be a great place to start from. Here at Orbital, our projects are vast and diverse, so it’s nice to have one set of lenses that we can build on in testing and pre-vis, and decide to move a certain direction when we eventually film.

Frank: Are there any focal lengths you favor over others, and are there any you want to get your hands on to test?

Leo: Our widest lens is a 24mm, and our tightest is an 80mm. We would love to have more lenses outside that range.

**********

For more more information about virtual production, visit Orbital Studios’ website.

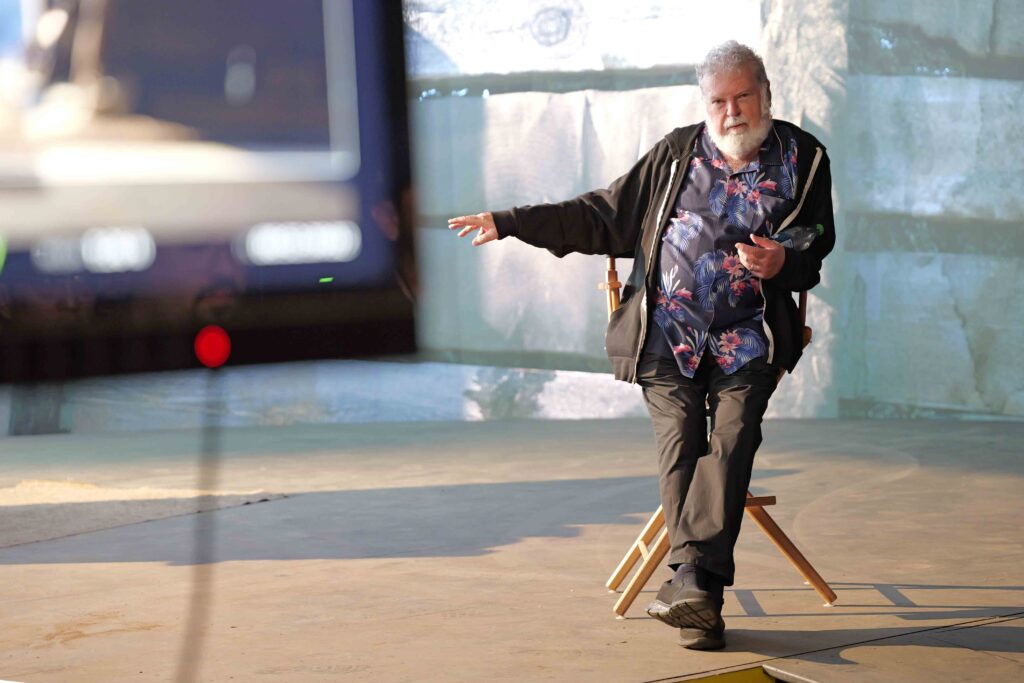

David, Robert, and the Dean

What do you do when legends in the field of cinematography field are sitting within reach of you, sharing all of their knowledge? Be in awe and hang on every word at the same time, of course. Orbital Studios hosted David Klein (The Mandalorian, The Book of Boba Fett), Robert Legato (Titanic, Avatar), and Dean Cundey (Jurassic Park, Back to the Future). Each providing unique insights into their process and live set examples.

David was very down to earth in his lecture. He was adamant that you do not have to know every aspect of how virtual production works. Rather, it is more important to know what each tool is capable of. He explained that in contrast to “normal” productions, virtual productions bring on cinematographers at least 5 months prior to shooting in order to work on pre-vis with the VAD, acquisition and volume teams.

Lighting is a complex aspect of filming on its own. Adding a virtual environment further increases the difficulty. Cinematographers must take care to not directly throw light onto the LED wall. Thankfully, planning and can be down during pre-vis. Using features within Unreal Engine, a cinematographer can walk through an environment using VR goggles and assess where lights should be placed. He made an interesting use of the LED walls themselves to add extra light boxes. Volume walls tend to perform better when used in slightly greater than median output. Any lower, and artifacts can be introduced. HMI units were also his preferred lighting fixtures as they interact well with subjects and the walls.

David highlighted the following reasons as to why productions choose to work on a volume:

- Impractical locations

- Scheduling

- Infinite magic hour

- Reduce physical set builds

- Control reflections

- Crowd scenes with fewer crew

During the pandemic, The Mandalorian and The Book of Boba Fett had to switch to completely virtual for pre-production. That dramatically changed the way the cinematographer and executives such as Jon Favreau interacted. By using VR Oculus headsets, producers could work from the comfort of their homes. Most of the pre-vis can be done by simply adding a color accurate monitor for referencing.

One tool to keep an eye out for in the coming years or months is ARRI Light Twins that allows for the use of virtual copies of real world lights and their qualities in a virtual environment with Unreal Engine.

Robert Legato has been a visual effects supervisor for some of the biggest films in cinema. His lecture covered creating concept tests to work out VFX processes. He stressed the importance of fighting to get say in any VP work because cinematographers must translate the creative elements of what must be included in the scene in ways that the volume engineers can understand. “Stops” and “nits” aren’t a one-to-one transfer, so being able to communicate competently to understand each other is critical.

Similarly to David, Rob also uses tools such as his phone in order to walk though an environment and make storyboards for pre-production. Storyboards, as useful as they are, should always come from a creative view and only for reference as things most often need to be adjusted on the fly.

Dean Cundey’s portion of the class was highlighted by a step-by-step demo of how to shoot a scene. It was interesting to see how professionally and calmly he was able to give direction to the crew and talent.

Dean was an extreme proponent of the methodology I mentioned earlier. Basing their VP approach not from a technical standpoint, but with fundamental principals of cinematography; being aware of the limits of the technology and working around them.

Note: This is unrelated, but Dean is one of the funniest people I have met, full stop. He effortlessly drops zingers and retorts that make the entire crew and class laugh.

The opportunity to learn and interact with high-level technology and instructors was truly an experience. For many, it can seem daunting to approach subjects such as virtual production without some instruction on how to properly break down the wall. Overall, the masterclasses offered by the ASC are incredible opportunities to learn and make deeper connections with fellows in the field.

Learn more about cinematography

The ASC holds master classes throughout the year. No class is exactly the same, nor are they focused on the same subject every time. They are incredibly insightful and valuable experiences for anyone interested in following the path towards becoming a cinematographer.