See full video below

Wide-Angle Lens Storytelling

Wide-angle lenses are amazing cinematic tools, bending light and capturing a wide field of view. Filmmakers have used them as long as film has been around, and before that, photographers used them to create images never before seen by the human eye. Today we’ll look how wide-angle lenses work, how they have evolved and how they can assist and enhance the craft of storytelling.

MM vs Field of View

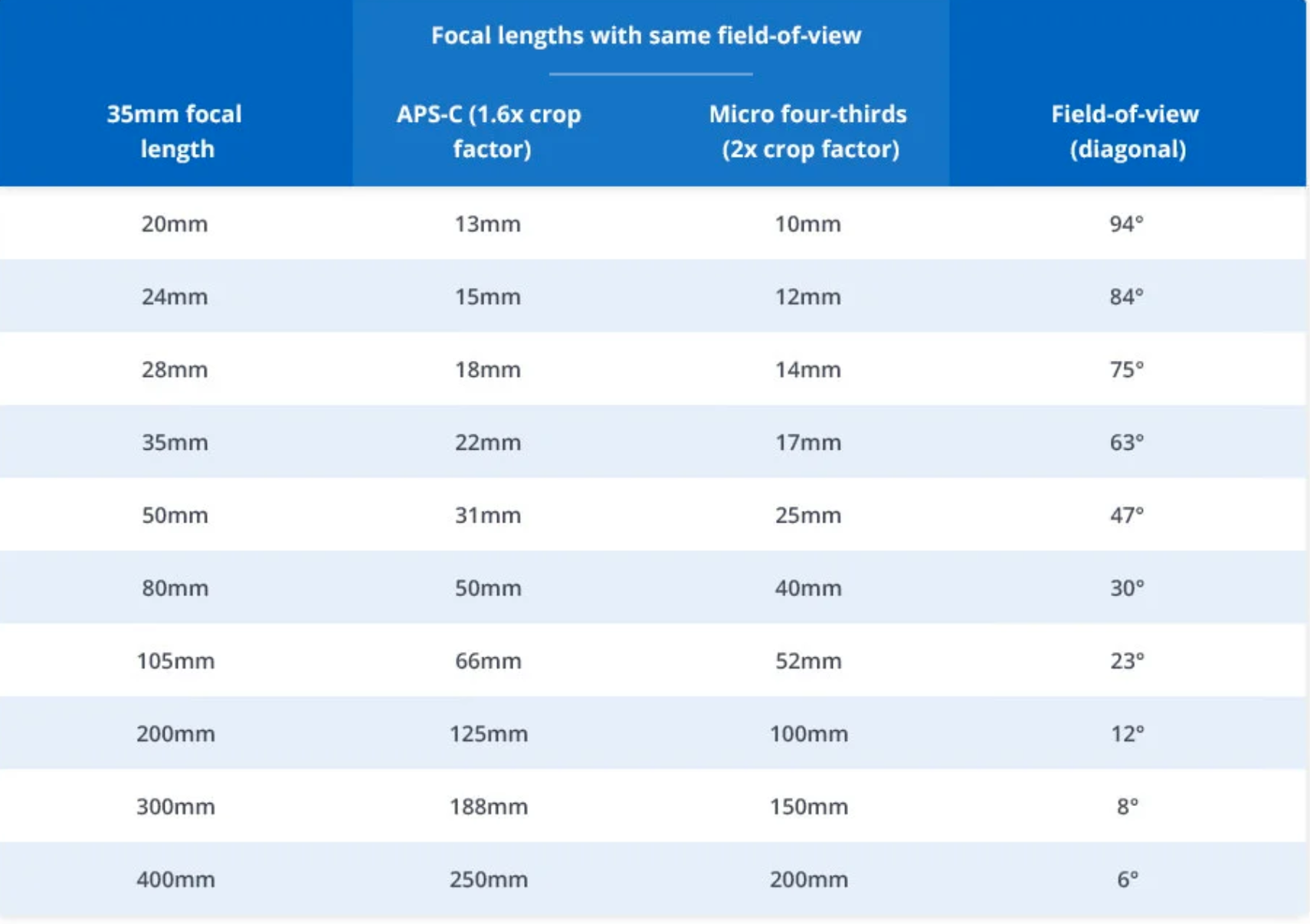

How “wide” a wide lens is will depend on several factors, including the size of the camera sensor. The millimeters of a lens, together with the size of the sensor or film, combine to give a field of view, or how much a given lens can see. Anything wider than around 65 degrees is generally considered to be a wide-angle lens, or smaller than a 35mm lens on a full frame camera.

The Hollow Orb

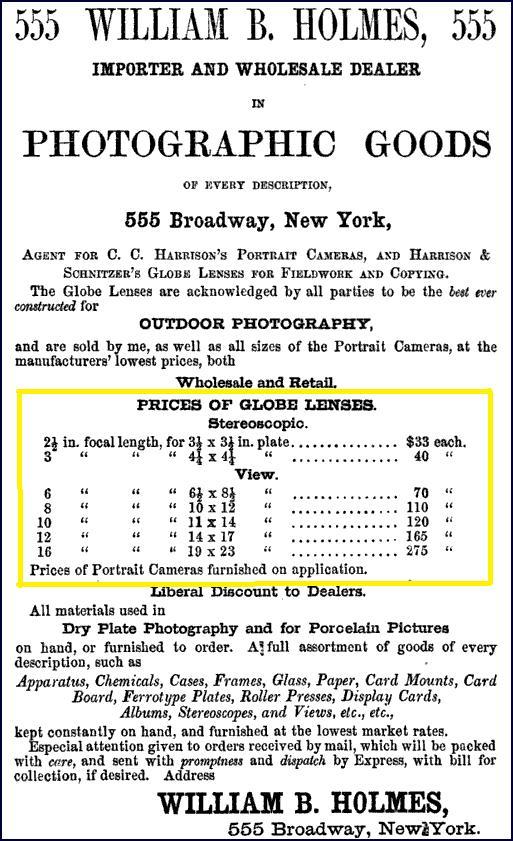

For centuries before a camera was ever constructed, people looked into clear marbles or drops of dew and were mesmerized by the whole world reflected back at them. Glass’s ability to bend light has always fascinated us, but it wasn’t until 1862 that the US company Harrison & Schnitzer created their “Globe” lens.

With a minimum aperture of f/16, it had a usable field of view of around 80 degrees, or the equivalent of a modern 22mm lens on a full frame camera. It was available for different plate sizes, all the way up to a large format 19 x 23″. It is interesting to see that the largest lens cost $257 in 1862 dollars, or the equivalent of $7000 today.

The Third Dimension

Filmmakers quickly learned that wide-angle lenses could help create optical illusions and assist them in the stories they wanted to tell. Wide angle lenses exaggerate space, making objects in front of the camera look further from the camera and from each other. It makes small rooms look bigger and large rooms look positively palatial. They enhance the subject by pushing the background away, almost to the horizon.

Early cinematographers took this effect to the next level, by moving the camera high and shooting down, making heights far higher than they appear to the naked eye. They also reversed this, putting the camera low and shooting up, elongating tall buildings.

The miraculous effects of the wide-angle lens do come at a cost. The periphery of the frame bends straight lines as its crams more onto the capture plane. The wider the lens, the more distortion is visible, and the more of a “funhouse mirror” vibe the lens creates. On Dutch tilts and other angles, the effect is even more pronounced, and the cinematographer has to balance the visual power of the image against the distraction caused by this side effect.

A second drawback of wide lenses is that you need to be comparatively close to your subject for them not to disappear into the background. This is sometimes an advantage, but in the age of multiple camera shoots, it means that cameras too easily find their way into the shots of other cameras. The most cameras with wide-angle lenses that can shoot the same scene at the same time is two, whereas with long lens cinematography, you can have as many as your budget allows.

Standing Tall

A trick that is still used in music videos today is to place a camera with a wide-angle lens on the floor and shoot up at the talent. It makes a normal-sized person appear tall and intimidating, and the ceiling more lofty. This can be enhanced by camera movement, by tilting up as the camera moves down at the same time as the subject stands up.

Free Real Estate

The “New Wave” of cinema in the 1970s was enabled by smaller, handheld, cameras that could move out of the studio and into real locations. These houses and apartments, unlike soundstages, didn’t have removable walls that let the camera move far enough back for a wide shot of the actors. Wide-angle lenses became indispensable for getting wider shots in smaller areas, and the distortion that came with it was adopted as a aesthetic choice.

Smooth Move

Another reason the New Wave filmmakers loved wide-angle lenses was how smooth they made handheld footage. Because objects appear further away, the shaking of the operators movement is much less noticeable on a wide-angle lens, and the wider the lens, the less movement is perceivable. With a 14mm or 20mm lens on a full frame camera, the handheld camera appears to glide through the air.

The World in a Single Frame

Despite the distortion they cause, or perhaps because of it, wide-angle lenses have undergone a renaissance in the last decade due to the work of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, also known as “Chivo”. Lubezki uses wide-angle lenses so he can photograph his subject and their environment in a single shot, which minimizes, even eliminates edits and other distractions from storytelling. In his Oscar-winning The Revenant, he used lenses between 12mm and 21mm on the wide Alexa 65 sensor to capture incredible imagery of characters pushed to their limits in an unforgiving wilderness.

Lubezki often shoots handheld, even with massive cameras, or uses long uncut Steadicam takes to capture epic action, like in the opening scene of The Revenant. They also won the cinematography Academy Award the year before for Birdman, an entire film made to look like a single take, shot on a S35mm sensor and 18mm lens.

Such a wide lens, once considered totally unsuited for character closeups because of the distortion created on faces, crafted a memorable film because the unbroken takes nurtured powerful performances.

Conclusion

Wide-angle lenses, around longer than Hollywood, have gone through multiple iterations, coming in and out of fashion as trends have changed. Today, thanks to their advantages for shooting long takes and handheld camera work, wide-angle lenses are never far from the camera of leading cinematographers.