Watch the full video below:

A full kit of lenses is usually on the top of every DPs gear list when they prep for a job, and its easy to see why. Which lens you use where is one of the biggest and most critical creative decisions made on a film set. It defines the “field of view” – what will be seen and what will be hidden. It’s one of the big factors that defines the style and tone of the film: something every creative filmmakers strives to do.

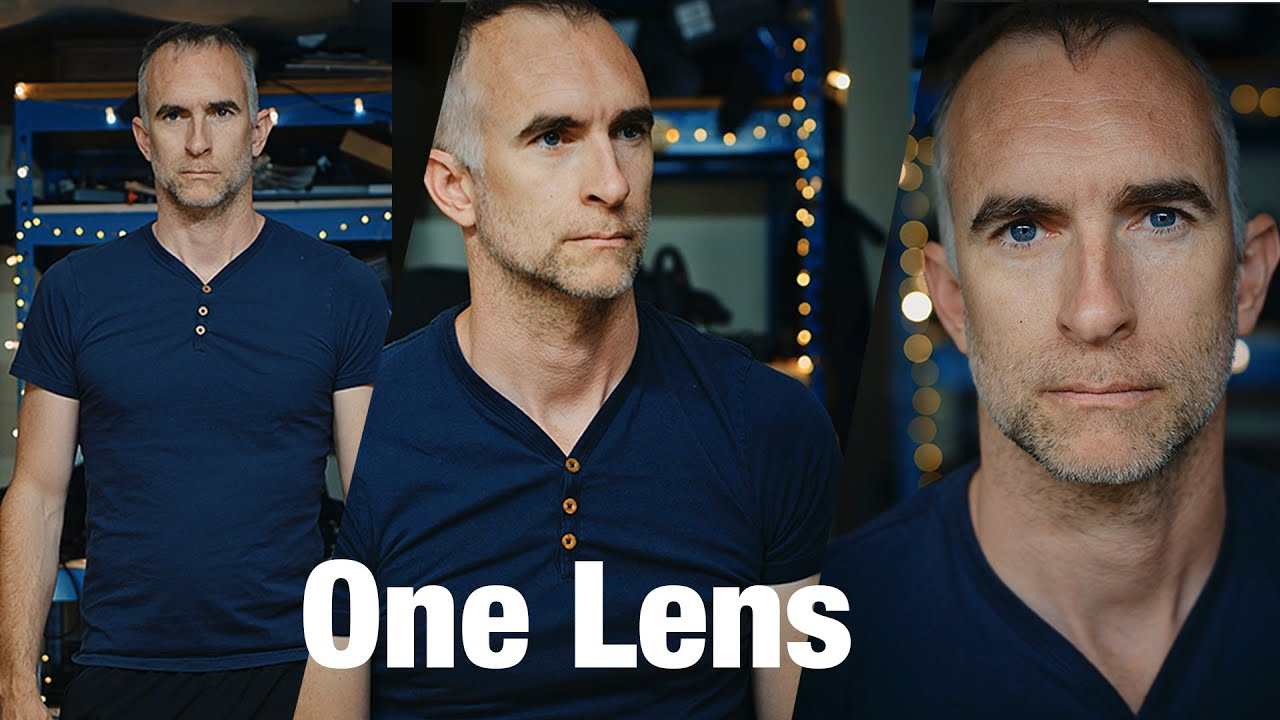

Shooting a closeup with a wider lens, a 24mm for instance as the Coen Brothers like to, elongates the features of the face but brings for more of the environment into focus, defining a character by their surroundings. Shooting closeups with a long lens, as many beauty commercials do, isolates the character and blurs the background into a dance of abstract light.

Even the term “cinematic” is commonly used on film sets to mean “non-naturalistic”, or to describe a heightened reality, and what better what to heighten the reality of your film than distort the very space that it occurs in? The properties of lenses, and changing between them, allows the filmmaker to alter how light is captured.

What if you only had one lens to shoot an entire feature film? How would the director and DP put a creative stamp on their setups without lens choice as a tool?

It might shock you to learn that many films have been shot with a single prime lens. Not for budgetary reasons, but because a single lens creates a unified aesthetic that the world of the film take place within. The choice NOT to chose is a powerful choice in itself.

One-shot films, notably Hitchcock’s Rope, used one lens because of the technical constraints of shooting long continuous takes don’t allow the filmmakers to change lenses between shots. This was also true of newer one take films, like Birdman (18mm) and Son of Saul (40mm), which had the ability to use a remote system to use a zoom lens, but chose not to.

Hitchcock was so impressed by the coherent feel the single lens on Rope that he shot Psycho on a single 50mm lens as well. Since Psycho, many thrillers have followed Hitchock’s lead and shot with one, or at the most, two lenses. One reason is that thrillers aim to manipulate the viewers nerves through clever pacing and editing, and purposely not manipulating space with lenses draws less attention to this, lulling the viewer into the sense that what they’re watching is an objective truth.

Using one lens also adds a sense of cohesion and unity to a project, bringing the different scenes closer together and putting the story more firmly in one voice. Since seeing the world through a new set of eyes is one of the joys of cinema, it’s no wonder that the single lens film is a powerful device. Shooting an entire film with one lens “establishes the rules of the game” and sets single perspective for the viewer to identify with.

So how can use use “one lens” filmmaking for your own projects, and what are the practical advantages? The lens has to be a prime, since using the different lengths of a zoom lens will give the same effects as swapping lenses. A cine lens is a must, since these lenses have a longer focus throw which lets the camera operator or focus puller get precise focus easily.

Since you are only using one lens, you can use the money you saved buying or renting an entire set to get the best quality available. It help to have a fast, high quality lens, such as SIGMA’s excellent Cine Primes, which give a wide open t-stop of 1.5. A fast lens will allow you to get proper exposure in low light and create a shallow depth of field when you need too.

Which focal length should you chose? Most single lens films have been shot on a super 35mm sensor, and most have used either a 35mm or 50mm lens. Of the one-take films, such as Birdman, The Wrestler, or Russian Ark, most use either a 18mm or 24mm.

It helps to have a small, moveable camera package, because you’ll be moving the camera back for wide shots and in for closeups, rather than swapping a lens. Because of this factor, it helps to work on sets with removable “wild” walls, or to have large locations, since how far you can get the camera from your subject is going to determine how wide your wide shots can be.

To adjust these lens size to a full frame sensor, such as the SIGMA fp, multiply the crop factor of the sensor by the millimeters of the lens. Most s35 sensors are a 1.5-1.6 crop, so a 50mm on a s35 will give the same field of view as a 75mm lens on a full frame camera.

The SIGMA fp also has a cool trick up its sleeve that makes a single lens film even more achievable, albeit at the cost of a unified perspective. It allows you to change between a full frame and s35 sensor mode, all while staying in 4K Raw or MOV recording. This means you can effectively change from a 35mm to a 50mm lens with the flick of a switch.

This is a great middle ground for a one lens workflow, because it allows you shoot wide establishing shots as well as beautiful closeups without compromising either, and while you still need to move the camera, you’ll only need to move it half as far to get the same shot.

Summary

Films made with a single lens have long been a powerful way to add a unified perspective to a story and draw the viewer in. With the introduction of full frame cameras like the SIGMA fp, with the ability to crop in to s35 sensor size and get a second lens length, its the perfect time to experiment with getting the best glass possible and bringing your own story to life.

Your math is going the wrong direction on crop. You write, “To adjust these lens size to a full frame sensor, such as the Sigma fp, multiply the crop factor of the sensor by the millimeters of the lens. Most s35 sensors are a 1.6 crop, so a 50mm on a s35 will give the same field of view as a 31mm lens on a full frame, which is close enough to 35mm. An easier way to do this is just move up or down one lens in a standard set. So a 120mm becomes a 75mm on a full frame, a 75mm becomes a 50mm and so on.”

A 35 mm lens will give a 56mm equivalent perspective on a 1.6 crop (35 x 1.5= 56). A 50mm will provide an 80mm view on a crop sensor. That’s an upside for bird documentarians because they can get closer to their subject with a less expensive zoom, but for cinema, it often means going down to an 18mm or 20mm lens to get to “street photography” views, and super wide shots can be frustratingly out of reach.

I like your point about the FP and changing camera modes to provide a “punch in” without losing resolution. It’s a fun workaround, and I’m going to try it on another camera system that provides dual modes.