The greatest thing about interchangeable camera lenses is the variety of optical designs, from ultrawide to supertelephoto and everything in between, that offer an incredible amount of variety for visual expression, creativity, and optical performance optimized for different photographic situations. And while it may be sometimes completely and totally obvious what types of photography a certain lens excels at—for example, everyone knows that Macros are designed to capture close-up details; telephoto lenses are great for long-reach wildlife and sports from the sidelines—many styles of camera lenses have lesser-known secret superpowers that can be called upon to make a photo. Let’s take a look!

Supertelephoto Lenses

Long lenses, like the Sigma 150-500mm F5.6.3, or 300-800 F5.6 to name two, are known to be great for making sports and wildlife images. Wide open, these lenses can isolate the subject from the background to really make the images pop. And of course, the wide apertures which give very shallow depth of field feel also yield the fastest shutter speeds, which are necessary to freeze a bird in flight, or an athlete on the move.

And Landscape, or should we say sky-scape, photographers also know that longer focal lengths also can make for huge suns and moons, the effect of which is amplified when the celestial orb is near earthbound features in the frame.

The Lesser-Known Superpower of Supertelephoto Lenses: Distance Compression

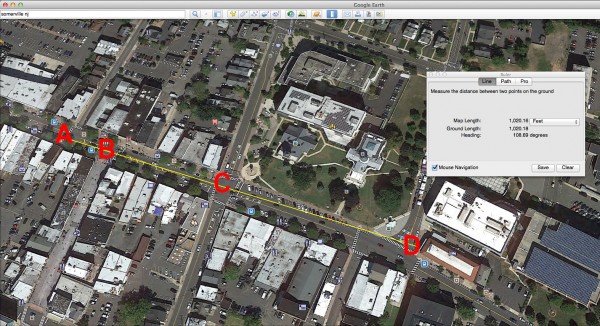

When supertelephoto zoom lenses are stopped down to smaller apertures, and focused at a longer distance, depth of field is increased, and the apparent relationship of distance between objects in the frame appears much more compressed than in a standard field of view.

The Achilles’ heels of telephoto compression

Stopping down a long lens to smallest apertures means you’ll need slower shutter speeds, so Optical Stabilizer or a tripod is often a must for this style of shot. And while the more you stop down the aperture, the greater the depth of field; going too far into the smallest diameter F-stops can introduce diffraction, which degrades total image quality. Slower shutter speeds mean that objects in the frame that are not totally stationary—branches blowing in the breeze, ocean waves, vehicles, clouds, and son on—may exhibit motion blur.

As you zoom to longest focal lengths, the field of view gets very narrow. You need pinpoint precision to align objects of interest at different distances from the camera. Changing position even slightly, a few feet this way, or a couple of yards that way can mean the difference between perfectly aligning the elements or not.

Ultrawide Lenses

Ultrawide lenses, of both the Fisheye and rectilinear variety, are wildly popular among landscape photographers, architectural specialists, and travel photographers for the ability to take in sweeping fields of view. These lenses are perfect for capturing sunsets that seem to go on forever; and capturing the total breadth and magnificence of buildings and monuments both ancient and modern.

The Lesser-known superpower of ultrawide lenses: super-close-up imaging

As you may know, close-focusing distance of a lens is measured from the sensor plane (which is marked on all cameras with this symbol: ø) and not the front of the lens itself. So, right off the bat, the wide-open close-focusing point is nearer to the front of the glass that it may first appear on the tech specs chart. For example, the Sigma 8-16mm ultrawide zoom lens is 4.2 inches long, and the close focusing distance is 9.4 inches. Add in the mount-to-sensor distance of 1.75 inches on a Rebel, and that’s close-focusing of just 3.45 inches in front of the front lens element wide open. Stopping down the lens to smaller apertures can cheat focus and depth of field to even closer to the front glass of the lens.

This can be very useful for situations where you need to be right on top of something to make an image, or to make a small nature feature the hero in the frame. While the total magnification doesn’t necessarily enter into the “true macro” classification, the significant depth of field can help place an object in a context, unlike a traditional macro shot which has a very thin slice of sharpness, even at smallest apertures.

The Achilles’ Heel

Again, diffraction is the challenge here. As much as you gain more an in-focus zone, stopping down too much counteracts the gains, as edges may not be sharp enough for bigger prints and presentations. Not very flattering for human subjects near the edge of the frame as the wide-angle field of views stretches and contorts.

Fast Standard Primes as Macros

A sharp, fast Fifty F1.4 is a beautiful thing—perfect for portraiture, documentary, and travel photography. The combination of focal plane sharpness, gorgeous bokeh, and field of view that nearly matches the human visual system can create astoundingly pleasing images that have a classic feel.

Lesser-Known Superpower: Lens-Flip Macro

In a pinch, many standard prime lenses can be reversed and held in front of the lens as a manually operated macro lens for capturing close-up details.

Achilles Heel of Lens-flip macro

Since the lens is not connected to the camera, there’s no way to adjust the aperture, so you’re shooting wide open at maximum aperture. You’ve got to be careful with the front element touching the lens mount to avoid scratches, and in dusty or sandy situations, it’s not the best idea to have the lens removed from the camera for extended periods of time.

Telephoto Macros for Longer-Distance Photography

Sigma offers three telephoto range F2.8 macro lenses with life-sized reproduction, a 105mm F2.8, a 150mm F2.8 and a 180mm F2.8 Macro. Each of these features Optical Stabilizer, a focus limiter, and internal focusing paired with close-focusing at 1:1 magnification. Obviously, these lenses are designed for, and excel at, close-up photography.

Lesser-Known Superpower

Some may not realize that everything about the design and build of these lenses makes them outstanding for longer-distance photography as well. In fact, the 180mm F2.8 Macro is just about the perfect mid-telephoto prime lens for birding or sports photography. The Autofocus limiter helps keep the focal range out of the macro zone for swifter long-distance response, and as a tele prime, the real-world samples are mind-blowingly sharp on the focal plane with very pleasing defocused rendering.

Achilles’s Heel of Macro for long-distance

There’s zero practical downside here. The only possible issue you may encounter is finding yourself needing to explain to other photographers why you’ve chosen a lens that’s designated as a Macro for longer-reach photography. And once they get it, they’ll get it, too.