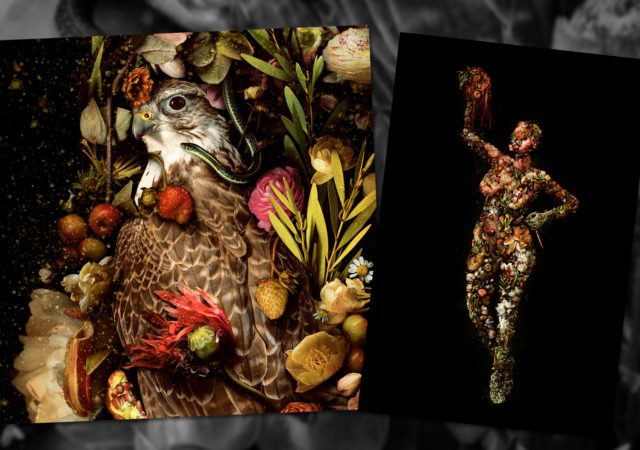

Artist Meggan Joy has spent years building beautiful digital collages with carefully-created photos of flowers, vegetables, and other natural elements. And with a SIGMA 70mm F2.8 DG Macro | Art lens in her kit, her work contains levels of detail that make her gallery prints something truly special to behold!

Macro Photography with a 600mm Telephoto Zoom Lens?

Macro photos with a telephoto zoom? It can be done! See how SIGMA Ambassador Heather Larkin uses the 150-600mm DG DN OS | Sports lens to capture beautiful close-ups of flowers, bugs and more.

Taking Photos for Take Your Child to Work Day

by Avery Howard This is a special guest blog post written and photographed by Avery Howard, 2nd grade daughter of Sigma’s chief blogger/tech editor, Jack Howard, for “National Take Your Child to Work Day” The first concept we got to…

The Sigma 180mm F2.8 EX DG OS HSM Macro Lens for Close-up Work

The Sigma 180mm F2.8 EX DG OS HSM Macro lens is the biggest, longest macro lens in the Sigma lens catalog. This telephoto lens offers true life-sized reproduction with a 1:1 maximum magnification ratio. Incredible sharpness—thanks to its state of the art optical design—Optical Stabilizer, and a three-zone focus limiter make this a serious lens for advanced macro photographers.

First Look: SIGMA 30mm F1.4 DC HSM | Art

The Sigma 30mm F1.4 DC HSM | Art lens replaces the very popular 30mm EX DC HSM lens as the fast, standard prime designed exclusively for DLSRs with APS-C sensors including the Sigma SD1 Merrill, the Canon EOS Rebel, 60D and 7D and a number of Nikon models including the D7100, D90, and D5100. And based on the updates and upgrades, the 30mm F1.4 Art lens is going to make a lot of photographers very happy.